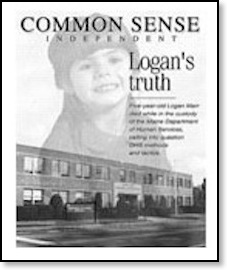

Logan Lynn Marr

Victim of Attachment Therapy

Chelsea, Maine

Killed January 2001 at age 5

Note: This account has been gleaned from published and broadcast news reports. See the webography for sources.

Sally Schofield thought that little Logan Marr was “a demon prone to fits of rage.” But Schofield, 41, of Chelsea, Maine, an experienced and “strong-willed caseworker,” also thought that she knew what was wrong with the 5-year-old: “Attachment Disorder.” (This is an unrecognized, overly-inclusive diagnosis that does not appear in the DSM.)

Schofield had had clients who had to deal with the same things that Logan, her foster daughter, was putting her through. Those clients had been taught parenting techniques and interventions, allegedly dealing with Attachment Disorder, prepared by Daniel Hughes, a prominent Attachment Therapy (AT) practitioner, author, and consultant to the State Department of Human Services. Schofield remembered what she had seen those clients do with their children and decided to deal with Logan in the same way.

It was a fatal mistake.

AT parenting techniques target disobedience, not lack of attachment, and especially don’t treat any real problems that reside in the relationship between parent and child. In the case of the relationship between Schofield and Logan, apparently a troubled one almost from the beginning, AT techniques led to continuous warfare between the two. At one point, Schofield told a babysitter that the issue between child and parent was about “who was in charge.”

Sally Ann Schofield in 2002, shortly before

her conviction for killing her foster daughter. She killed the girl

while practicing AT techniques, philosophy and principles

she had picked up second-hand as a

state fostercare caseworker.

[Photo: WGBH Boston]

AT parenting insists that mothers win all battles over control. As evidence later presented at trial shows that Schofield would “get frustrated” and “dig in” when things didn’t go her way. For her part, Logan decided that she didn’t like Schofield, and would complain about her to her birth mother when they visited. (Those visits, by contrast, were calm and sedate affairs). By the visitation rules, the birth mother was not allowed to respond to, or even to acknowledge, the child’s complaints.

Logan also reacted to her treatment by throwing tantrums. Schofield would then escalate with even more AT parenting. One of the techniques used was putting the 5-year-old into a baby’s high chair. Logan wouldn’t sit still for it. On 31 January 2001, Logan was especially loud in resisting the high-chair treatment. She and the chair were moved to the basement. The tantrum continued. According to the judge who tried the case, “Logan’s defiance infuriated Sally Schofield to the point that she secured Logan to the high chair by wrapping layers of duct tape around Logan’s torso and behind the back of the chair to prevent her getting out.” That left Logan with only one outlet to express her displeasure. “To silence her screams, [Schofield] wrapped more duct tape under her chin, over her head and across her mouth…then [she] left Logan to struggle against her bonds in isolation” in the basement.

Logan Marr, reported to be in one of her “rages.”

She was presumed to be acting out with her foster mother

as a result of “Attachment Disorder.” Prominent AT proponents

claim every adopted and foster child has AD

as a consequence of poor nurturing

by an unfit birth mother.

[Photo: WGBH Boston]

When Schofield later checked on Logan—by some accounts more than an hour later—the girl was dead. Medical examiners concluded she had suffocated. Before calling for emergency services, Schofield removed the duct tape and hid it. Police investigators later found 40 feet of it—with tufts of Logan’s hair still stuck to it.

Facing a charge of depraved indifference murder, which carries a sentence of 25 years to life imprisonment, Schofield and her lawyers sought out any exculpatory explanation: blame-the-child (“she bound herself in duct tape”), undetected medical problems (“some fluke cardiac thing”), a seizure, and—in line with AT advocates around the country—the birth mother.

The judge trying the case without a jury rejected all of these defenses. He called the self-wrapping “as preposterous as it is incredible.” There was no credible evidence supporting the cardiac or the seizure notions. And he agreed with the prosecutor’s angry rebuttal that “Christy Marr had nothing to do with duct-taping that child in the basement.” He ultimately sided with the prosecution’s conclusion that Logan had been asphyxiated as a result of Schofield’s conduct.

The judge didn’t agree with the prosecution’s murder charge, however, and convicted Schofield of manslaughter instead. She was “unquestionably reckless,” in her treatment of Logan, especially at the last. As an experienced caseworker, he said, she knew better. He sentenced her to 20 years in prison, where she is today. The sentence, in the mid-range for manslaughter, satisfied the prosecution, who saw no basis for leniency. “I haven’t seen one iota of acceptance or responsibility on the part of that woman,” declared the lead prosecutor after the original verdict.

The usual AT tactic of vilifying the birth mother backfired in this case. As more public attention was drawn to the case, first statewide in Maine, then nationally (culminating with a PBS Frontline documentary — see the webography below), it became increasingly apparent that Logan may have been wrongfully taken from Christy Marr (whose surname now is Reposta). While the shifting public attention from Schofield’s conduct to DHS’s conduct helped to lower AT’s profile in the case, at the same time it served to undermine the “Attachment Disorder” diagnosis for Logan’s behavior, which rests on an assumption of bad treatment by a birth mother.

Christy M. Reposta

talking to PBS’s Frontline. Though she never

abused or neglected her two daughters,

she had them taken away by the state

for failing to keep away

from Christy’s own mother.

[Photo: WGBH Boston]

While Reposta was not a model mother and provider for her children, neither was she an abuser or neglectful. The actual reasons given for taking away the children was Reposta’s alleged “failure to protect” them from possible child abusers, including Reposta’s own mother. Ironically, Reposta believes it was her mother that made the initial reports that brought the family to the DHS’s attention.

Reposta’s relationship with her mother had always been stormy. Even so, it was difficult for her to obey completely the DHS’s requirement that the family not have any contact with her mother. As it became more difficult for the young mother to make ends meet, it was especially hard to be cut off from her only outside support—her mother. It was only a matter of time, then, that she would run afoul of the state’s dictates. DHS eventually found out about the transgressions and they moved quickly to take the children.

The state was also determined to go much further. Not only did it put the children into foster care, but it wanted to terminate Reposta’s parental rights and put the children up for adoption. It was arranged for Schofield to adopt them as soon as they were available.

It was this institutional eagerness to terminate parental rights, even in a case where neglect or abuse was not an issue, which caused a public sensation, first statewide in Maine, then nationally (culminating in a PBS Frontline documentary—see the Webography below). One critic characterized the DHS’s attitude as “take the children and run.”

Whatever the merits of DHS’s decision in the case, the resulting controversy underscored the vacuity of one of AT’s prime tenets: that all foster (and adopted) children are Attachment Disordered as a result of the bad treatment received at the hands of birth mothers. Logan’s alleged behavior had all the characteristics of AD that AT advocates point to, but her history belied that diagnosis.

Logan may have been a troublesome child to her foster mother, but it was not because of mal-attachment. If anything, it appears that she might have been “parentified” — a condition where a child feels she has to take on adult responsibilities — which confused and scared her. Yet she was treated as if she had “Attachment Disorder,” which would only reinforce the child’s parentification judgment. The outcome was tragic, all the more so because it was avoidable.

There is one understated aspect to this case. The State of Maine (or at least its DHS) officially recognizes the diagnosis of “Attachment Disorder,” despite the fact that there is no reputable professional recognition of it. In the wake of Logan Marr’s death, and of the public revelations of her treatment by Sally Schofield, the state has partially disclaimed the use of Holding Therapy (which is AT by another name) and the use of restraints on children. Nevertheless, it still endorses Attachment Therapy (by that name) and makes referrals to Attachment Therapists if asked. As mentioned above, it has employed a leading AT advocate, Daniel Hughes, as a consultant.

AT is alive and well in the State of Maine. Alas, Logan Marr is not.

___________________________________________________________________

Read more...

- Sally Schofield. [Interviews with police investigators], 2001 [excerpts on Frontline website].

- Ruth-Ellen Cohen, “DHS curbs use of holding therapies,” Bangor Daily News, 26 Apr 2001, p A1

- Paula Gibbs, “Babysitter told Logan’s death was ‘fluke cardiac thing,’” Boothbay Register, 20 Jun 2002

- Tess Nacelewicz, “Foster mom charged and convicted in foster girl’s death,” Portland Press Herald, 26 Jun 2002

- Clarke Canfield, “Former Maine adoption caseworker sentenced to 20 years for death of her foster daughter,” Associated Press, 26 Sep 2002

- Barak Goodman, “The Taking of Logan Marr,” Frontline, 30 Jan 2003