Schmitz Case

18 Children

10 adopted children, 1 biological

7 with unknown legal custodian

Victims of Attachment Therapy Parenting & Rehoming

Rescued June 2004

Green Bay, Wisconsin, and Trenton, Tennessee (Gibson County)

NOTE: Several elements of this case strongly suggest the

involvement of Attachment Therapy/Parenting in the abuse of these children,

as well as being an example of its practice of “re-homing.”

Note: This account has been gleaned from published and broadcast news reports. See the webography that follows for sources.

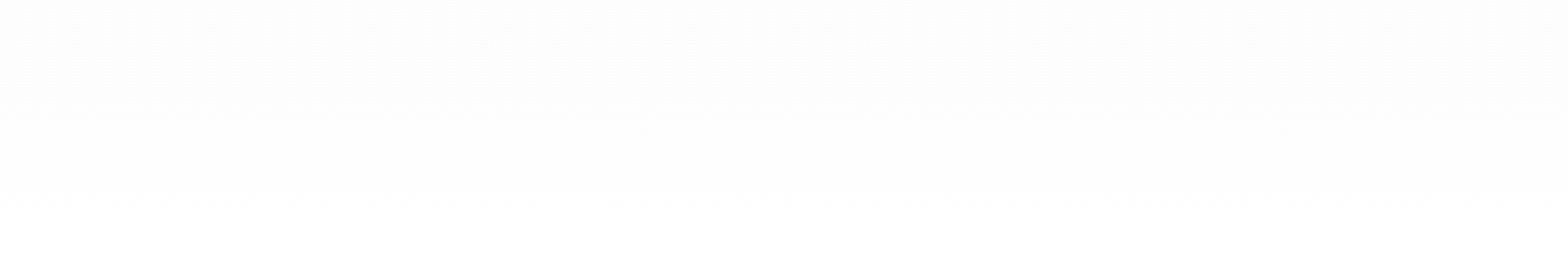

Debra Schmitz was sentenced to only 6 months in jail; Tom Schmitz received one year of

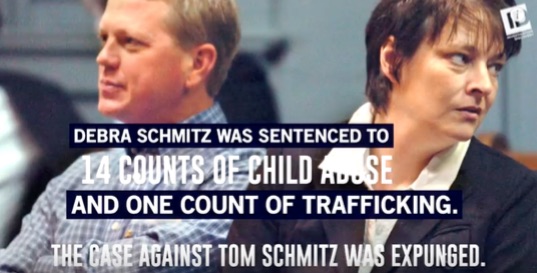

probation after which he record would be expunged. Watch interview with Nora Gateley,

one of the now-adult children abused in the Schmitz home on Investigation Discovery.

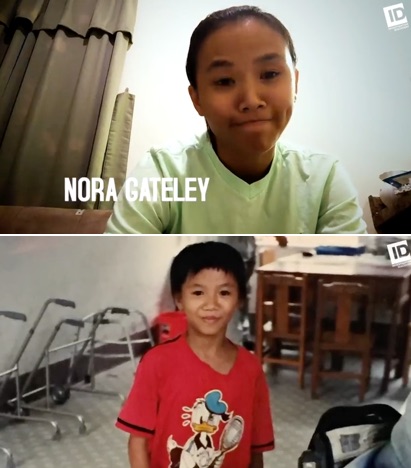

In September 2004, after a grand jury review, Tom Schmitz, 45, and Debra Schmitz, 44, were indicted on 54 charges of aggravated child abuse, trafficking children, and operating a child care agency without a license. While the charges were drastically reduced, and the Schmitz received very light sentences, the judge in their case told them that he believed their motive for getting more and more children was “greed, not love.”

Authorities investigating allegations of abuse found 18 children in the Schmitz home, ranging in age from 1 to 17. Mrs. Schmitz told a visiting nurse that she could get a child off the Internet in three weeks without going through child welfare agencies. So sorting out legal status of these children, also proved a challenge for investigators.

Four years earlier, the Schmitzes had moved from Green Bay, Wisconsin, to a farm in rural Gibson County, Tennessee. Tom worked as a sales manager for a portable toilet rental business, and Mrs. Schmitz homeschooled some of the children, most of whom were classified as “special needs” children. “Most” had been diagnosed with “Reactive Attachment Disorder” (RAD). Uncharacteristic of the actual disorder, the Schmitzes characterized children with RAD as being unmanageable and violent. Mrs. Schmitz stated that 80% to 90% of her work online involved Attachment Therapy; she advertised herself an expert in Attachment Therapy and took in children from families that shared this interest.

Attachment Therapists commonly diagnose adopted children with “Attachment Disorder” (AD), a condition only recognized by Attachment Therapists. AD is usually conflated with RAD, a rare disorder with professional recognition. With “a majority” of the children diagnosed as having “RAD,” the Gibson County Department of Children’s Services had the children evaluated. Their spokesperson Carla Aaron explained, “Reactive attachment disorder is a diagnosis that is widely thrown out there. Research shows that a lot of these kids that have been diagnosed with that really don’t have it. It’s a possibility that these children weren’t properly assessed, so we wanted to get an independent diagnosis.”

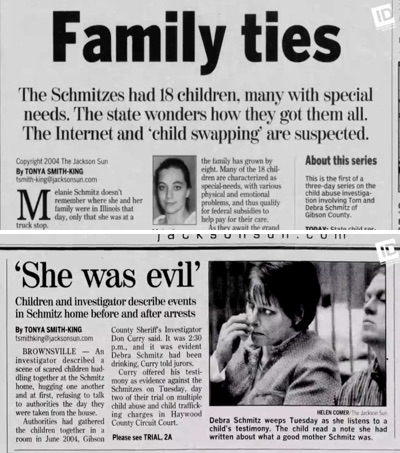

Because of the medical challenges of some of the children, two visiting nurses – Sherry Dvorak and Brenda Filkel – from the agency Care All, were brought in to help. When they became alarmed at conditions in the home, Dvorak arranged for two children who approached her for help to record their allegations of abuse which, together with the nurses’ statements, triggered investigation by the authorities.

The allegations were many. They included claims that Mrs. Schmitz beat the children; kept some children in a cage, while others were locked in unlit, cellar rooms; that the children were inadequately fed and improperly medicated; older children were put into diapers; and children were required to do long hours of sitting on the floor facing a wall [what Attachment Therapists call “Strong Sitting”].

One girl adopted by the Matthews but living with the Schmitz family testified she had been forced to sit all day and half the night in horse manure. When one girl would not reveal the name of a boy who passed her a note in school, Mrs. Schmitz cut her hair in short clumps (1 to 3 inches) after each refusal to answer. One adoptee from China was punished by having her leg brace taken away from her, which she needed to walk because of damage done in early childhood by polio. Another child was forced to sleep naked on the floor after breaking a vase.

Other claims were that Mrs. Schmitz threw a knife at girl, hitting her in the shoulder, and that both parents held down a girl to lance a boil with a “rusty box cutter.” Children with special medical needs were neglected. More allegations were revealed later to the press: Holding a child’s head under water; sitting on top of and urinating on a child; forcing a boy to eat his own vomit; hitting children in the face and head with a wooden paddle; throwing a disabled child into a swimming pool that was iced over; and making one child walk naked in front of the other children. Tom is alleged to not have helped the child thrown into the pool; put a garden hose in the mouth of a girl and turned on the water; put dog feces in a girl’s hair and forcing her to leave it there for several hours; and whipping a girl on bare buttocks.

The public was stunned to learn that both Tom and Debra Schmitz were also accused of forcing children to dig their own grave. Evidence of four such graves was found by investigators. Ten years later, now-adult child Nora Gateley claimed that ten or more of the children had been forced to do this while Mrs. Schmitz threatened them with death, telling them “no one would care.”

With in a few weeks, 16 children living with Frances and Dale Matthews, neighbors of the Schmitzes, were also removed because of allegations of abuse and neglect. Investigators learned the two families had been close and exchanged children. One of the Matthews adopted girls was living in the Schmitz home, and the Schmitzes planned to adopt her.

Investigators found the ten adopted children in the Schmitz home had been taken on through private arrangements; there was one biological child; and status of seven others was unknown. These children had been “rehomed,” i.e. they had been passed from one home to another, sometimes several times, or back and forth. The investigation, which started out in Tennessee and Wisconsin, would involve several other states in attempts to find the children’s legal guardians.

The Schmitzes had adopted children from Florida, New York, Wisconsin and Tennessee. Informal arrangements were responsible for the presence of seven more, variously from New York, Michigan, Louisiana, Texas and Tennessee. Months later, the authorities were still trying to locate a girl who had once been part of the Schmitz (and Matthews) household, but had been “shipped out” to Arizona to a woman studying to be an Attachment Therapist.

Investigators learned the Schmitzes moved from Green Bay shortly after being investigated in that state for child abuse. The accusations in Wisconsin were that children had been forced to sleep on the bathroom floor; stand under cold showers; some were locked for two days in a bedroom, being fed only bread and water; and one child had been tied to a bed. And as in Tennessee, there were allegations that Mrs. Schmitz drank heavily. No charges were filed in Wisconsin.

Jerry Heston, a pediatrician and child psychiatrist, was the prosecution’s expert witness. He described the harm the abuse in the Schmitz house had done to the children: fearfulness, lowered self-esteem, depression, high anxiety, distrust of adults, hopelessness, anger, humiliation, and trouble sleeping.

Virginia Attachment Therapist Ronald Federici was initially hired by the prosecution to examine the children. (Federici bills himself as a expert in the area of adoption.) But he was introduced to the court as a defense expert witness, perhaps because he claimed only two or three of the children had RAD and that most have severe brain damage or mental disorders that made them unreliable witnesses. The prosecution was unsuccessful in barring Federici as an expert witness, and he testified that neither of the Schmitzes fit the profile of a child abuser. But he agreed that if the alleged abuses were true, they could cause emotional and mental harm.

In a retrial in July 2006, Mrs. Schmitz plead no contest and received a 6-month jail sentence for 15 counts of “severe child abuse,” with the sentences running concurrently. (She was released early for good behavior.) Tom got one year of probation, after which his record can be wiped clean. However, the outcome is believed to keep the Schmitzes from regaining their parental rights.

Were the Schmitzes remorseful? Probably not. They launched a yellow-ribbon campaign, suggesting the 18 children taken from their home had become “hostages” of an uncaring system. But one of the children’s former nurses has countered with a blue-ribbon campaign in support of the children.

BACKGROUND

Reactive Attachment Disorder

During the time the Schmitzes lived in Green Bay, the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, under the leadership of Reggie Bicha, listed Attachment Therapists as approved providers. This state agency funded the aggressive promotion of Attachment Therapy through organization such as Adoption Resources of Wisconsin (ARW). This organization had a lending library for adoptive parents that contain a complete collection of Attachment (Holding) Therapy materials, including tapes on parenting by the infamous Connell Watkins and Nancy Thomas.

It’s no surprise that were two Attachment Therapy centers in the Green Bay area during the four years the Schmitz family resided in Wisconsin: Christian Counseling Ministries (CCM), of Howard, and Renaissance Trauma and Recovery Center (RTRC).

CCM declined to talk to the press, other than to deny using the more brutal methods of Attachment Therapy. (A promotional video of therapy at CCM shows a young boy being held by his parents on a sofa while a therapist taps the sides of the child’s head.)

The Green Bay Press Gazette interviewed Attachment Therapist Helen Roberts from RTRC (which is apparently no longer operating). Asked about RAD, she instead described Attachment Therapy’s unrecognized diagnosis (“Attachment Disorder” or AD) which is commonly conflated with RAD.

“They may go into a rage and put holes in walls or kick and hit mom,” Roberts said. “It looks like mom doesn't know how to control them but in actuality the child doesn't have any internal controls.” She claimed children with RAD need stricter discipline than other children, with the goal being a more compliant child. Echoing an Attachment Therapy mantra, Roberts said, “By the time they are done with treatment, they are more respectful and responsible and fun to be around.”

The Green Bay Press Gazette included a side box on “What is reactive attachment disorder?” that listed AD’s bogus signs (rather than those of RAD, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association). The list was the taken from RTRC’s website:

Behaviors include: obsessing with gore or fire; showing extensive oppositional behavior toward the mother; defecating or urinating in odd places; smearing feces; acting overly “cute” with strangers and overly affectionate with people other than the parent; pitting people against each other and telling different versions of the same story to try to get people in trouble; being manipulative; lying about things that are obvious; needing to control every situation whether obvious or covert; blaming others; showing hyperactive and impulsive behavior; raging for up to four hours; having a sense of entitlement; not realizing that a behavior leads to a consequence. The reactive attachment disorder child may have good street smarts, and they make very good con artists.

The Michigan adoptive mother, Karen Tolin, who sent her “RAD” child to live with the Schmitzes 18 months before being removed by authorities, told the Jackson Sun that some of the alleged abuses in the Schmitz home are parenting techniques necessary for children with special needs. Her daughter was one of the children allegedly kept locked in a cage and subjected to cold showers. Asked her opinion of that treatment, Tolin said those are recognized techniques for treating “RAD.” The Schmitzes intended to adopt Tolin’s daughter, but Tolin now doesn’t want her going into the foster system.

“Rehoming” Children

One of the more bizarre aspects revealed by investigators was the apparent practice of “rehoming” or trafficking children. With the discovery that the Schmitzes did not have legal custody of seven children — and authorities had trouble finding out who did — the case revealed the shadowy world of Attachment Therapy’s “therapeutic respite,” one of it abusive parenting techniques and money-makers.

Children diagnosed with “RAD,” may qualify for “special needs” subsidies. (Ronald Federici, expert witness for the defense, told the press that the records he reviewed revealed the Schmitzes were receiving $8,000 to $9,000 each month in subsidies.) Like the Schmitzes, people involved in Attachment Therapy are known to have connections that enable them to take in children for extensive “respite” in two ways:

- By privately adopting children directly from other adoptive parents who no longer wanted their children; and

- By private arrangements to lodge children. This is claimed to be “respite,” though respite is normally understood as taking a child for just a few days or weeks. (In Tennessee, foster parents are allow up to 31 days a year for respite and a maximum of three special needs children.) One boy found staying with the Schmitzes under a respite arrangement had been there four years.

Mothers with “RAD” children form a network of virtual communities on the Internet where they are part of secretive online “support groups.” They call each other “Awesome Mom,” compare notes, brag about who is the strictest disciplinarian, complain about their “RADishes,” share tips about how to deal with CPS, and swap sympathy — and their children.

Mothers in these support groups often complain of exhaustion. When they tire of a child, the group responds by recommending AT “therapeutic respite” to break through the child’s “wall of resistance.” The child may stay in respite for a short period, years, or never return.

Children can get stuck in respite when the respite provider reports poor progress on the part of the child, or when the parents are reluctant to take the child back. In any case, respite providers end up with the child and the subsidy funds. These children can be tossed from respite home to respite home, never knowing when or where their next move might be. This is done deliberately to keep “RAD” children “off balance” so they are “unable to manipulate others.” It is another indicator that Attachment Therapy/Parenting is all about establishing total control over children and little, if anything, about creating affectionate ties between parent and child.

The furtive nature of all this in the real world is illustrated by a story how the Schmitzes got possession of one of the children. One day, the entire family loaded into a motor home and traveled from Green Bay to an Illinois truck stop. There they were handed a young boy about 7 years old. Ironically, this happened around the same time as the Schmitzes were honored by the Green Bay YWCA with a “Families of Distinction Award” for their “work with children with special needs.” The boy at the truck stop was reportedly one of those removed from the Schmitz home in June 2004.

The connection between Attachment Therapy and trafficked children was visible in a 2013 investigation of “rehoming” by the international news organization Reuters. They identified 271 online posts advertising children, mostly foreign adoptees, who were up for grabs. We here at Advocates for Children in Therapy looked at those ads and found that 36% specifically mentioned “RAD” or “AD.” That percentage went up to 51% if you added in those who mentioned “attachment” or “bonding” problems.

Webography

NBCNews interview, 9 Sept 2013, with Nora Gateley about

being adopted and then “rehomed” to Tom and Debra Schmitz.

- “Extreme Tough Love” When adopted children are incorrectly diagnosed with attachment disorder, things can go very, very wrong, by Kathryn Joyce, 6 Mar 2014, Slate.

- “Parents use underground network to hand off unwanted adopted children,” 9 Sep 2013, NBC Nightly News.

- “Adopted girl says mother forced her to dig her own grave,” 9 Sep 2013, NBCNews.

- “Girl, given up by adoptive parents, made to dig own grave in abusive new home,” Doyle Murphy, 9 Sep 2013, NBC Nightly News.

- “Debra Schmitz, convicted of child abuse, was released from jail in November,” Jackson Sun, 20 Jan 2007

- “Mother Begins Serving Child Abuse Sentence,” Wave News, 20 July 2006

- “6 months in jail for Schmitz,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 11 July 2006

- “Judge declares mistrial in Schmitz case; new trial set for July,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 7 Feb 2006 [in archives]

- “Adopted son defends Schmitzes,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 3 Feb 2006

- “7 charges in Schmitz case dropped,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 2 Feb 2006

- “’She was evil’: Children and investigator describe events in Schmitz home before and after arrests,” Jackson Sun, 1 Feb 2006

- “Expert witness testifies about possible psychological damage to children in Schmitz home,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 1 Feb 2006

- “Children take the stand as Schmitz trial begins,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 31 Jan 2006

- “Testimony heard in day two of the Schmitz Trial,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 31 Jan 2006

- “Jury seated in Schmitz trial; some counts dropped,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 30 Jan 2006

- “Schmitz boy wasn't coerced, judge rules Gag order also issued until trial is over,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 24 Jan 2006

- “Enclosed beds cause controversy,” Wendy Koch, 17 Jan 2006, USA Today.

- “No state fully compliant with child-welfare standards,” Wendy Koch, 18 Jan 2006, USAToday.

- “Underground network moves children from home to home,” Wendy Koch, 18 Jan 2006, USAToday.

- “Schmitzes’ charges may be reduced,” (with timeline) Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 11 Jun 2005

- “Judge won’t step aside in abuse case,” Tijuana Cheshier, Jackson Sun, 4 Mar 2005

- “Matthews convicted of child abuse,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 4 Dec 2004

- “Abuse Cases: Marianna Matthews,” 11 Nov 2004, Pound Puppy Legacy.

- “Schmitzes’ lawyers say witnesses inconsistent,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 2 Oct 2004

- “More to 'mega families' than just raising kids,” Jackson Sun opinion, 1 Oct 2004.

- “Schmitzes free on $500,000 bond,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 1 Oct 2004

- “Officials discuss ‘mega families’,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 30 Sep 2004

- “Schmitzes return to jail in abuse case,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 29 Sep 2004

- “Schmitzes indicted on child abuse,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 28 Sep 2004.

- “Schmitzes’ hearing delayed,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 3 Sep 2004.

- “Child Abuse in Two Huge Tennessee Families Investigated,” Pound Puppy Legacy, 2 Sep 2004

- “State penalized for keeping evidence from Schmitz defense,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 31 Aug 2004.

- “Foster mom backs Schmitzes,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 31 Aug 2004.

- “A Special Report: The Schmitzes,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 31 Aug 2004.

- “A ‘failure to bond,’ but how to fix it?” Lee Renisch, Green Bay Press Gazette, in Jackson Sun, 30 Aug 2004.

- “A Special Report: The Schmitzes,” Part 3 of 4, Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 30 Aug 2004.

- “A Special Report: The Schmitzes,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 29 Aug 2004.

- “Schmitzes may see new child abuse charges,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 15 Aug 2004.

- “Schmitz case at a glance,” Jackson Sun, 15 Aug 2004.

- “DCS takes 16 children from home,” Tonya Smith-King, Jackson Sun, 31 Aug 2004.

- “Affidavit spells out child abuse allegations against Schmitzes,” George Metaxas, WMC-TV Memphis, 9 Jul 2004.

- “Child-abuse complaints an inexact science: Schmitz case focuses attention on process,” Lee Reinsch, Green Bay Press Gazette, 2 Jul 2004

- “Foster couple charged with abuse, neglect,” Woody Baird, 1 July 2004, Associated Press.

- “18 Children in care of Tom and Debra Schmitz,” 30 June 2004, Pound Puppy Legacy.

- “Couple who took in 18 kids booked on abuse charges,” 25 June 2004, Associated Press.

- “Affidavit Alleges Abuse by Tenn. Couple,” Associated Press, 2004.

- “Child-abuse case may revive Brown County probe Ex-Howard couple face Tennessee charges,” Lee Reinsch, Green Bay Press Gazette, date unknown.

“Dark Side of Adoption,” 2 Feb 2019, Investigation Discovery.

Interview with Nora Gateley, one of the children abused

in the Schmitz house.

More articles about the Schmitz and Matthews cases can be

accessed from the Jackson Sun archives.